Building Bridges of Trust for Virginia’s Newest Refugee Families: A Practical Guide

by Kate Ayers

Virginia doubled the number of refugees that it resettled in this fiscal year, resettling 4,381 people in Charlottesville, Richmond, Hampton, Roanoke, Harrisonburg, and Northern Virginia (Refugee Services, n.d.). The majority were from Afghanistan, making Virginia one of the top 5 states across the United States to resettle Afghan evacuees.

Hearing all of the traumatic evacuation stories of the newly arriving Afghan community has reminded me the importance of trauma informed care. The sheer numbers of Afghans who resettled in Virginia means that many new faith communities and volunteers are stepping up to help and cross-cultural communication may be new to them. As a previous special education teacher, I understand the struggle to meet both the educational and emotional needs of students. I recently heard Dr. Suzy Ismail at the Cornerstone family counseling services speak and was inspired by how her work could be translated to the classroom.

Understanding the History

Virginia has been informally resettling refugees1 since the 1930s when the first group of Jewish refugees arrived in Richmond, but the refugee resettlement program that we know of was not formalized until 1980 with the passing of the Refugee Act. This program has had bipartisan backing from its inception until 2016, but Virginia has been welcoming refugees from across the globe ever since.

Understanding the Current Landscape

Prior to October 2021, Virginia’s resettlement program had been cut in half due to the previous administration’s immigration policies. This meant that when hundreds of thousands of people were evacuated from Afghanistan in the fall of 2021, the resettlement system had a lot of catching up to do.

Virginia doubled the number of refugees that it resettled in this fiscal year, resettling 4,381 people in Charlottesville, Richmond, Hampton, Roanoke, Harrisonburg, and Northern Virginia (Refugee Services, n.d.). The majority were from Afghanistan, making Virginia one of the top 5 states across the United States to resettle Afghan evacuees.

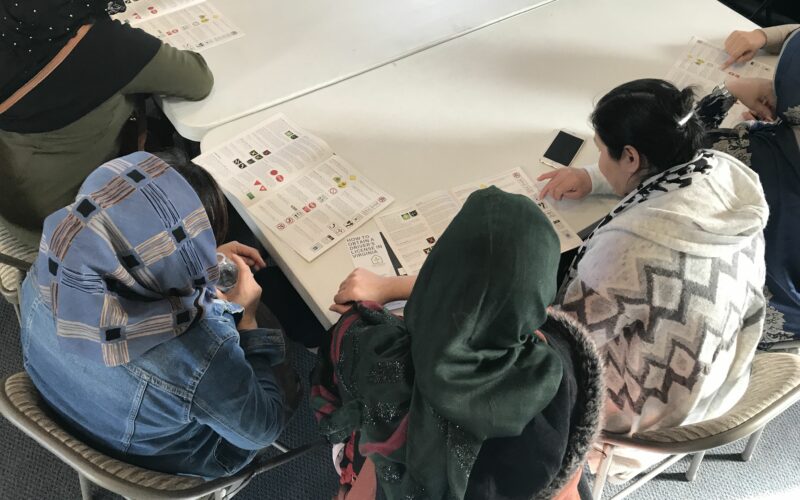

As this newest group of newcomers come into your classroom, honing your trauma-informed care and cultural competency strategies will be essential to develop the trusted relationships needed to foster a positive learning environment.

Understanding the Trauma: Triple Trauma Paradigm

When it comes to trauma-informed care, teachers must start by understanding the full story of their students’ experiences. Understanding the “Triple Trauma Paradigm” (Beckman et al., 2005, pp. 22–23) can help you better understand the extent of trauma that your students experienced and are still experiencing. This paradigm divides the refugee experience into three stages where different kinds of traumatic experiences occur:

Pre-Flight: The conditions that lead to someone deciding to flee their home could include harassment, experiencing or witnessing violence, loss of job or housing, food insecurity, living underground, imprisonment, and/or societal chaos.

Flight: When people leave their home and are seeking safety, they can experience fear of being caught and having to return; living underground; illness; separation; isolation, crowded, and unsanitary conditions; long waits; great uncertainty of the future; and loss of home and possessions.

Post-flight: When people reach their destination and try to resettle in a new place, they may experience unsatisfactory societal and economic conditions; transportation, language, and cultural barriers; racial/ethnic discrimination; family separation; shock of new climate and geography; inadequate/dangerous housing; unemployment/underemployment; bad news from home; and/or loss of identity/roles.

It is important to understand that your students who had to evacuate from Afghanistan experienced additional layers of trauma during their flight and post-flight stages. Many Afghans got on an evacuation plane with no more than the clothes on their backs and had to live on U.S. military bases for months before being allowed to resettle permanently. Because so many people needed to be resettled in a short period of time, the post-flight stage has been more traumatic than normal due to capacity limitations in resettling communities. Housing shortages, long waits for healthcare appointments, and delayed school enrollment will all impact the students walking through your door.

Understanding the Culture: Collective vs. Individualistic Cultures

(Brown, 2021)

While it is impossible to understand and adapt to all the cultural nuances your students bring into the classroom, striving to be more culturally aware builds bridges of trust with your students.

A good starting point for being more culturally aware is to start with knowing if your students are from a collective or individualistic culture. While the United States is individualistic, most displaced people tend to come from collective cultures (Ballard et al., 2016, p. 5.3). In the rest of the article, I will highlight a few tenets of the collective culture and specific strategies to use that will lead to building more trust in your classroom.

-

- Tenet: The power differential between student and teacher tends to be much larger for collective cultures.

Strategy: Integrate choice into lessons to give the student some power in their learning, but create boundaries around the choices so that the student isn’t overwhelmed by the number of choices. When students insist on calling you a formal name, go with it. Lessons that require students to question or debate the teacher may not work as well. - Tenet: Collectivist cultures typically have less personal space (except for division between genders) and prefer working as a group. Sharing answers may be construed as cheating in an individualized society but may be viewed as supporting one another in a collectivist culture.

Strategy: Allow for the students to work together and allow them to move physically toward one another during group work. Be clear when you want them to work on their own and not share answers. - Tenet: Collectivist cultures are polychronic, meaning time is fluid. Being on time and understanding the value that Americans put on time is a learning curve that your students must overcome when resettling in the United States.

Strategy: Understand that their tardiness does not typically equate with disrespect—be patient and help them overcome this learning curve by designing lessons to help them understand how Americans typically value time. - Tenet: Collectivist cultures tend to be more visual and focus on the context rather than the content of the communication.

Strategy: You need to focus more on tone of voice, eye contact, facial expression, and body positioning (nonverbal cues) of your students. These are more accurate indicators of how they feel as opposed to the words they are using. (And use visuals as much as possible!)

- Tenet: The power differential between student and teacher tends to be much larger for collective cultures.

Building trust with anyone (especially individuals who have experienced trauma) takes time. It is easy to want to bypass this relationship building when you understand how far the student may need to go before becoming English proficient.

ReEstablish Richmond is a local nonprofit with the mission to connect refugees to the resources they need to establish roots, build community, and become self-sufficient. For more information or to find out how to get involved, visit: www.reestablishrichmond.org. (We always need ESL tutors!)

1It is important to acknowledge that the data in this article only reflects individuals who qualify to receive benefits through the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The numbers do not reflect the thousands of asylees and asylum seekers who have also had to flee their homes due to violence, human rights violations, and persecution but have not been able to obtain immigration status that allows them the same benefits.

References

Ballard, J., Wieling, E., Solheim, C., & Dwanyen, L. (2016). Immigrant and refugee families (2nd Ed.). University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/immigrantfamilies/chapter/5-3-mental-health-treatments/

Beckman, A., Choe, J., Lennon, E., Lundberg, A., Northwood, A., & White, C. (2005). Working with torture survivors. In the National Capacity Building Project at the Center for Victims of Torture’s, Healing the hurt: A guide for developing services for torture survivors. (pp. 19–38). The Center for Victims of Torture. https://www.cvt.org/sites/default/files/u11/Healing_the_Hurt_Ch3.pdf

Brown, G. (2021, July 30). Difference between collectivism and individualism. Difference Between Similar Terms and Objects. http://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/difference-between-collectivism-and-individualism/

Refugee Services. (n.d.). Virginia Department of Social Services. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.dss.virginia.gov/community/ona/refugee_services.cgi

Kate Ayers joined ReEstablish Richmond in 2013, motivated by her participation in the “Just Faith” program, a class focusing on social justice issues around the world. Holding a master’s degree in teaching, she previously worked as a special education teacher and department chair in Hanover County for 11 years, while also serving as a volunteer mentor for refugees in the Richmond community. Kate is currently a member of the Office of New Americans Advisory Board, and her dedicated efforts continue to build a supportive, trustworthy community for refugees and new immigrants living in Richmond.

Kate Ayers joined ReEstablish Richmond in 2013, motivated by her participation in the “Just Faith” program, a class focusing on social justice issues around the world. Holding a master’s degree in teaching, she previously worked as a special education teacher and department chair in Hanover County for 11 years, while also serving as a volunteer mentor for refugees in the Richmond community. Kate is currently a member of the Office of New Americans Advisory Board, and her dedicated efforts continue to build a supportive, trustworthy community for refugees and new immigrants living in Richmond.